MACE Potential

Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) provides a powerful framework for constructing high-order polynomial basis functions to describe atomic environments. Many existing descriptors, such as SOAP, MTP, HBF, and ACSF, can be seen as special cases of ACE. While ACE is highly flexible and comprehensive, it is limited by its cutoff distance, which restricts the range of interactions it can model.

In ACE, high body order polynomial basis functions are constructed to describe the local environment of an atom:

where is the state of atom at time , and are the basis functions. The basis functions are constructed using a set of one-particle basis functions, which are then symmetrized to ensure they respect the symmetry properties of the system.

To overcome this limitation, message passing neural networks (MPNNs) can be used to describe atomic environments. However, MPNNs are computationally expensive and challenging to parallelize across multiple GPUs.

Multi-Atomic Cluster Expansion (MACE) combines the strengths of ACE and MPNNs. It is an E(3)-equivariant (translation, rotation and reflection), atom-centered neural network that extends ACE by incorporating message passing. The key idea is to use ACE models to parameterize the many-body messages . MACE achieves excellent performance and generalization while being faster to train and evaluate compared to other machine learning potentials. The E(3)-equivariant neural network is constructed by the e3nn package.

In this section, we will first explain the construction of ACE features and then show how MACE extends this framework.

Feature Construction¶

To describe the environment around a central atom , we start with one-particle basis functions . These functions capture the spatial arrangement of neighboring atoms and are built using three components:

- Radial basis functions (): Depend on the distance between the central atom and its neighbors.

- Spherical harmonics (): Capture angular information about the arrangement of neighbors.

- Chemical attributes: Incorporate information about the types of atoms involved.

By combining these components, we can represent the interaction between the central atom and its neighbors.

Next, we construct atomic basis functions by summing over contributions from all neighbors. These functions are invariant to the permutation of atoms. To capture more complex interactions, we extend these to higher-order atomic basis functions () by taking products of the lower-order ones.

To ensure the basis functions respect rotational symmetry, we symmetrize them to obtain . These symmetrized functions are then used to compute messages (), which encode information about the atomic environment. The resulting messages are both permutation-invariant and rotation-equivariant, making them ideal for use in MACE.

Message Passing¶

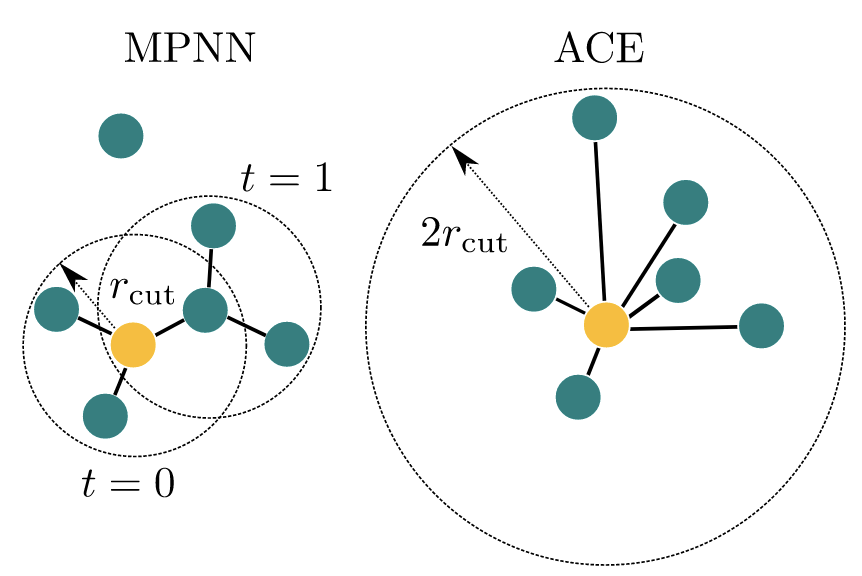

Message passing is the process of sharing information between atoms to update their features. It consists of three main steps: message construction, feature update, and readout. Message passing can be considered as a sparsification of an equivalent ACE model with a much larger cutoff radius.

The left panel shows a cluster with two iterations message passing process (MACE) with a cutoff of . The right side shows the cluster a cutoff radius of (ACE). The MACE model can be seen as a sparse version of the ACE model, where only the nearest neighbors are considered for message passing. This allows MACE to capture long-range interactions while maintaining computational efficiency. Figure adapted from Batatia et al. (2025)

Message Construction¶

At each step, the state of an atom is described by:

- Its position (),

- Fixed attributes like its chemical element (),

- Learnable features () that evolve during the process.

To share information, messages are passed from neighboring atoms to the target atom . The message is constructed by combining information from all neighbors. This ensures the process respects both the order of atoms (permutation invariance) and their orientation in space (rotation equivariance).

In MACE, the message is built using the symmetrized atomic basis functions (). These functions describe the environment around atom and are combined with learnable weights (). Clebsch-Gordan coefficients are used to ensure the message respects the symmetry of the system.

Update¶

Once the message is constructed, it is used to update the learnable features of atom . This update step adjusts the features based on the information received from neighbors. The updated features continue to respect the symmetry properties of the system, ensuring consistency throughout the process.

Readout¶

After several rounds of message passing and feature updates, the final state of each atom is used to calculate its energy. The energy is computed by summing contributions from all steps. This ensures the energy calculation respects the symmetry and order of the atoms, making it accurate and reliable.

- Drautz, R. (2019). Atomic cluster expansion for accurate and transferable interatomic potentials. Physical Review B, 99(1). 10.1103/physrevb.99.014104

- Batatia, I., Kovács, D. P., Simm, G. N. C., Ortner, C., & Csányi, G. (2022). MACE: Higher Order Equivariant Message Passing Neural Networks for Fast and Accurate Force Fields. arXiv. 10.48550/ARXIV.2206.07697

- Batatia, I., Batzner, S., Kovács, D. P., Musaelian, A., Simm, G. N. C., Drautz, R., Ortner, C., Kozinsky, B., & Csányi, G. (2025). The design space of E(3)-equivariant atom-centred interatomic potentials. Nature Machine Intelligence, 7(1), 56–67. 10.1038/s42256-024-00956-x