Workflow

High-throughput simulation involves a systematic and automated workflow, typically comprising the following stages:

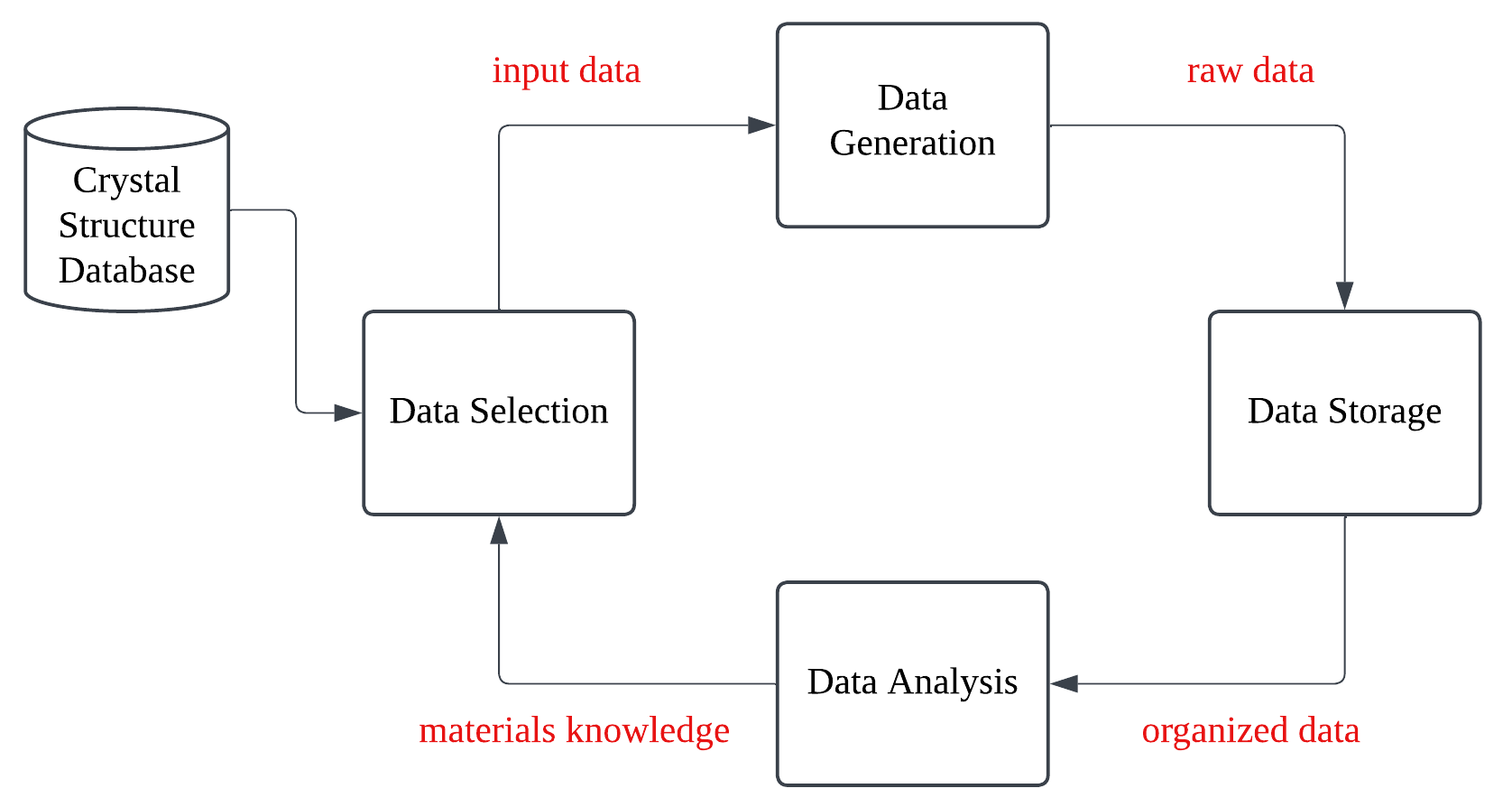

Workflow of high-throughput simulations: data selection, generation, storage, analysis, and whole iteration process. A crystal structure database can be used in data selection process. Reproduced from Jain et al.

Data Selection: A large and diverse set of candidate crystal structures is created. This is the starting point for our computational exploration. There is usually an external crystal structure database that contains atomic positions and lattice paramters of known mateirals and can be used as a starting point for generating new structures.

Data Generation: The properties of interest (e.g., energy, electronic structure, mechanical properties) are calculated for each generated structure using appropriate computational methods, such as density functional theory (DFT) or force field simulations. They’re computed in parallel to speed up the process.

Data Storage: After the generation of the data, the raw output files are sent to an efficient data storage/retrieval system (i.e. a database). This is crucial for managing the large volume of data generated in high-throughput simulations.

Data Analysis: The calculated data is analyzed to identify structures that meet specific criteria (e.g., stability, desired band gap, high bulk modulus). This step often involves visualizing data and applying selection rules.

The results of the screening process can be used to guide further data selection or to refine the computational parameters. This iterative feedback loop allows for a more focused and efficient exploration of the materials space.

Data Selection¶

We need to define the materials or systems we want to simulate. The foundation of any high-throughput study is the generation of a representative set of candidate structures.

From Crystal Structure Databases¶

We can start by selecting structures from existing databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), Cambridge Structural Database (CSD), or Crystallography Open Database (COD). Please see our previous lecture. These databases contain experimentally determined crystal structures of a wide range of materials. By filtering based on specific criteria (e.g., space group, composition, properties), we can create a diverse set of starting structures. It is also possible to use the computed structures from databases such as the Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW, or other materials databases.

Elemental Substitution¶

Using established crystal structure prototypes (e.g. perovskites, spinels, rock salt) as starting points. These prototypes provide a structural template. By systematically substituting different elements into the crystallographic sites (A, B, and sometimes the anion site), a large number of derivative structures can be generated. Databases such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) serve as valuable resources for identifying known prototypes and their structural parameters.

Once a prototype structure is chosen, elemental substitution is a powerful technique to explore compositional variations. For instance, starting with the perovskite SrTiO3, one could systematically replace Sr with other alkaline earth metals (Ca, Ba, Mg) to generate CaTiO3, BaTiO3, and MgTiO3. Similarly, Ti could be replaced with other transition metals (Zr, Hf, etc.). This can be done on multiple sites simultaneously, leading to compounds like SrTiZrO3.

Another example is considering the search for new transparent conducting oxides (TCOs). Starting with the known TCO In2O3 (which adopts a bixbyite structure), researchers might substitute In with other elements like Ga, Al, or Sn, systematically exploring the (In, Ga, Al, Sn)2O3 compositional space.

Combinatorial Approaches¶

It is also possible to use combinatorial approaches to generate new structures using known building blocks. For example, one could combine different layers or building units to create new 2D materials. This approach is particularly useful for exploring complex materials with multiple components or layered structures.

If the structure is disordered, one can use advanced methods such as cluster expansion or Monte Carlo simulations to explore the configurational space. These methods are particularly useful for studying solid solutions, alloys, and other disordered materials.

Random Structure Generation¶

In contrast to methods that rely on known prototypes or systematic substitutions, random structure generation aims to explore the structural space in a more unbiased way. This approach is particularly useful when little is known about the likely structure of a material, or when searching for entirely new structural motifs.

The basic idea is simple:

Define a Unit Cell: Specify the size and shape of the unit cell (which may be variable).

Randomly Place Atoms: Place atoms of the desired elements within the unit cell at random positions.

Constraints (Optional): Impose constraints to ensure the generated structures are physically reasonable (e.g., avoiding atomic overlaps, maintaining charge neutrality).

Random structure generation can be implemented using various algorithms and software packages. It often requires a large number of generated structures to adequately sample the relevant regions of the structural space. This is often combined with a structural relaxation step (using DFT or a force field) to bring the randomly generated structures to a local energy minimum. The example code is the AIRSS (Ab Initio Random Structure Searching) method is a widely used approach that combines random structure generation with DFT calculations to explore the potential energy landscape of materials.

Low-fidelity Screening¶

Before diving into high-throughput simulations, it’s often useful to perform a low-fidelity screening to filter out materials that are unlikely to be of interest. This can be done using simple criteria from the key chemical concepts and element properties in the search for candidate materials with target properties. For example, one might exclude compositions that are not charge-neutral, have too many atoms in the unit cell, or contain toxic elements. This step helps reduce the size of the search space and focus computational resources on more promising candidates. SMACT (Semiconducting Materials from Analogy and Chemical Theory) is an example of a low-fidelity screening tool that uses chemical intuition to identify promising materials. More constraints can be found below:

Avoiding Atomic Overlaps: Generated structures should not have unrealistically short interatomic distances, which would lead to extremely high energies and unphysical configurations.

Charge Neutrality: For ionic compounds, the overall charge of the unit cell should be zero. This requires careful consideration of the formal charges of the constituent ions.

Chemical Intuition: Prior knowledge about chemical bonding and stability can be used to guide the structure generation process. For example, certain element combinations are known to be immiscible or to form specific types of compounds.

Coordination Preferences: Certain elements tend to favor specific coordination environments. For instance, oxygen often prefers tetrahedral or octahedral coordination with metal cations. Enforcing these preferences can improve the likelihood of generating stable structures.

Targeted Property Constraints: More sophisticated constraints can be used to target materials with specific properties. For example, one might enforce a specific band gap range or a desired magnetic ordering.

Thermodynamic Stability: Generated structures should be thermodynamically stable under the relevant conditions (e.g., temperature, pressure). This can be assessed using phase stability diagrams or other thermodynamic models.

Data Generation¶

This part is often the most computationally intensive. It involves running the simulations for each generated structure, typically using high-performance computing resources. Automation is key to managing the large number of simulations efficiently. Tools like workflow managers (e.g., FireWorks, AiiDA) and job schedulers (e.g., SLURM, PBS) are used to distribute and monitor the simulations.

Simulation Setup¶

Setting up the input parameters for each simulation, such as:

- Use the right level of theory for the calculations (e.g., DFT, force field, tight-binding).

- Exchange-correlation functional, basis sets, and k-points sampling for DFT calculations.

- Force field parameters, timestep, and ensemble for Molecular Dynamics.

- Temperature, pressure, and Monte Carlo moves for Monte Carlo simulations.

Automation Scripts¶

These scripts handle the submission of jobs, data transfer, error handling, and post-processing tasks. They ensure that the simulations are executed correctly and that the results are collected and organized for further analysis. Scripts are usually written in Python or shell scripting languages.

If the simulations are computationally expensive, it is common to use approximations or lower-level methods for the initial screening. Promising candidates can then be selected for more accurate (and expensive) calculations.

Parallelization¶

High-throughput simulations often involve running a large number of calculations in parallel to speed up the process. This can be achieved by distributing the calculations across multiple processors or nodes on a high-performance computing cluster. Parallelization can significantly reduce the time required to complete the simulations.

Workflow Management Systems¶

Workflow management systems provide a higher-level interface for defining and executing complex workflows. They allow for the creation of multi-step pipelines, error handling, and provenance tracking. These systems are particularly useful for coordinating simulations across multiple software packages and computing resources. Examples include FireWorks, AiiDA, or any other custom workflow system. We will discuss more details in Codes.

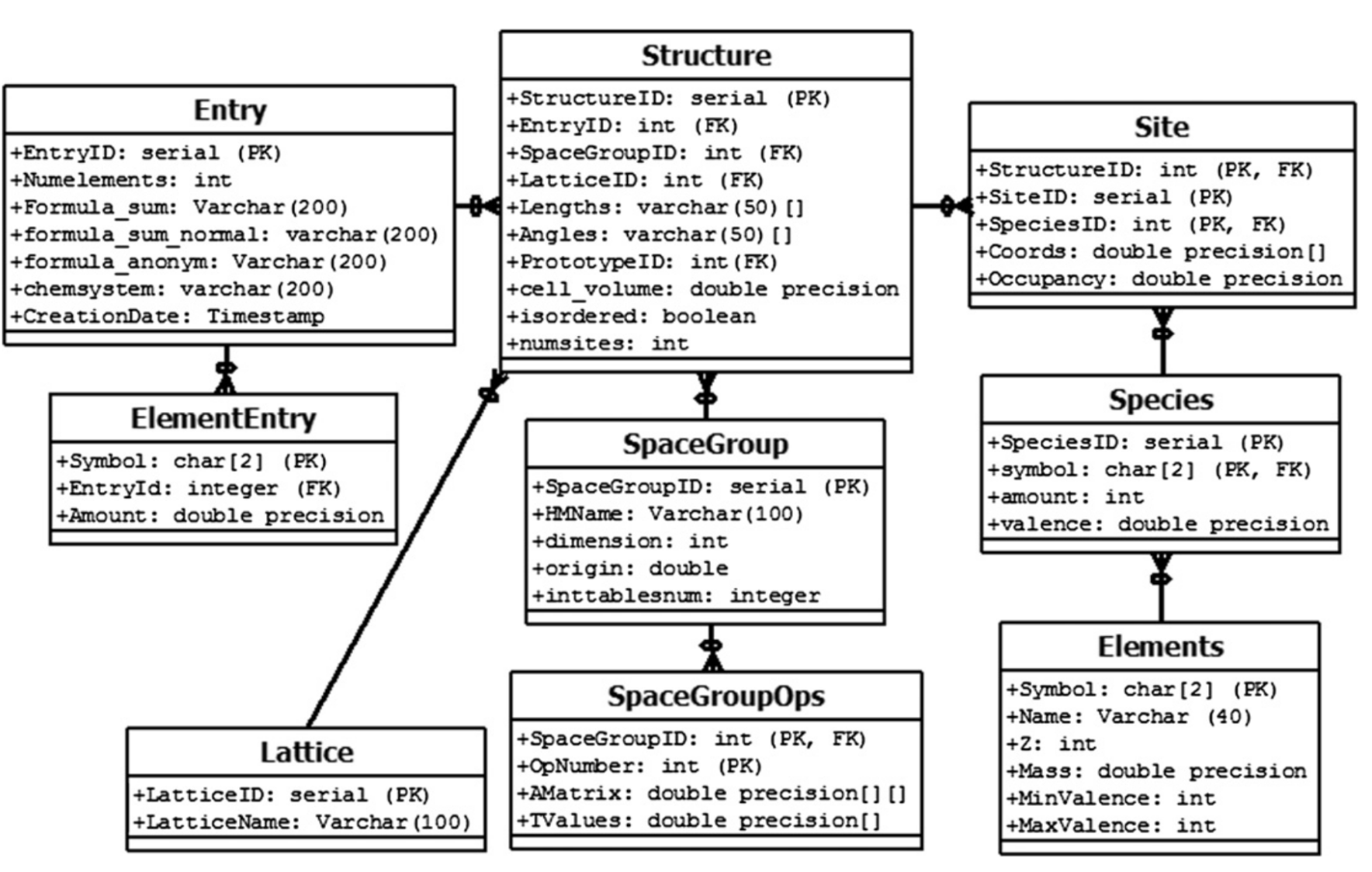

Data Storage¶

Data flow diagram for high-throughput simulations: data is generated, stored, and analyzed in a structured manner. Reproduced from Jain et al.

Once the simulations are complete, the data needs to be collected, organized, and stored for analysis.

Parse and Extract Data¶

Relevant data from the simulation output files needs to be extracted and parsed. This can include energies, forces, stresses, electronic structure information, etc. Tools like ASE, pymatgen, or custom parsers are used for this purpose.

Database¶

The extracted data is typically stored in a database for easy retrieval and analysis. For smaller dataset, simpled structured file formats such as .json, .csv, hdf5, or .xyz can also be used. For large dataset, databases like MongoDB, PostgreSQL, or custom SQL databases are commonly used. The choice of database depends on the type and volume of data being generated.

Data Cleaning and Organization¶

Keep track of the input structures, simulation parameters, codes, and versions used for each simulation. This is crucial for reproducibility and data integrity. Organize the data in a structured way to facilitate analysis and visualization.

Data Analysis¶

This is where we extract knowledge from the simulation data. Various analysis techniques can be applied to identify trends, correlations, and interesting structures. Visualization tools help in interpreting the data and communicating the results effectively.

- Thermodaynamic Analysis: Phase stability diagrams, convex hulls, and free energy calculations are used to determine the most stable structures under given conditions.

- Visualization: Plotting tools like Matplotlib, Plotly, or VESTA are used to create graphs, phase diagrams, crystal structures, and other visual representations of the data.

- Statistical Analysis: Statistical methods can be used to quantify the relationships between different properties and to identify outliers or anomalies.

- Machine Learning: Advanced techniques like machine learning can be employed to predict properties, classify structures, or cluster similar materials based on their properties.

Iteration and Refinement¶

The insights gained from data analysis often lead to new hypotheses and further simulations. We might refine our search space, explore new compositions or structures, or use more accurate (and computationally expensive) methods for promising candidates identified in the initial screening. This iterative loop is key to efficient materials discovery.

- Jain, A., Hautier, G., Moore, C. J., Ping Ong, S., Fischer, C. C., Mueller, T., Persson, K. A., & Ceder, G. (2011). A high-throughput infrastructure for density functional theory calculations. Computational Materials Science, 50(8), 2295–2310. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2011.02.023

- Davies, D. W., Butler, K. T., Jackson, A. J., Morris, A., Frost, J. M., Skelton, J. M., & Walsh, A. (2016). Computational Screening of All Stoichiometric Inorganic Materials. Chem, 1(4), 617–627. 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.09.010