Site Property

In crystallography, a site property is a fundamental concept that describes the physical and chemical characteristics of specific atomic positions within a crystal. Imagine a crystal as a well-organized orchestra where each atomic site contributes its unique “sound.” These individual characteristics, influenced by their local environments, determine the overall performance of the material under varying conditions such as temperature and pressure.

The detailed understanding of a site property enables scientists and engineers to interpret how local differences at the atomic level aggregate to form complex material behaviors.

Positions¶

Understanding coordinate systems is fundamental in crystallography as they provide a framework for describing atomic positions within a crystal.

Fractional Coordinates (u, v, w)¶

Fractional coordinates are used to express the positions of atoms relative to the unit cell dimensions. Each coordinate (u, v, w) is a fraction of the unit cell’s edge lengths along the crystallographic axes. This system is particularly useful for describing periodic structures because it inherently accounts for the repeating nature of the crystal lattice. For example, a fractional coordinate of (0.5, 0.5, 0.5) indicates that the atom is located at the center of the unit cell.

Cartesian Coordinates (x, y, z)¶

Cartesian coordinates, on the other hand, describe atomic positions in absolute terms, typically measured in units such as Ångströms (Å) or nanometers (nm). These coordinates are more intuitive for visualizing molecular structures and for performing calculations that require precise distances and angles. In this system, the position of an atom is given by its distance along the x, y, and z axes from a defined origin point.

Conversion Between Coordinate Systems¶

Converting between fractional and Cartesian coordinates is a crucial skill in crystallography. This conversion is performed using the lattice vectors of the crystal, which define the unit cell dimensions and angles. The relationship between the two coordinate systems can be expressed mathematically, allowing scientists to switch between the abstract periodicity of fractional coordinates and the tangible geometries of Cartesian coordinates.

For example, if the lattice vectors are defined as a, b, and c, the conversion from fractional (u, v, w) to Cartesian (x, y, z) coordinates can be performed using the following equation:

where: (x, y, z) are the Cartesian coordinates, (u, v, w) are the fractional coordinates, are the components of the lattice vector a, are the components of the lattice vector b, are the components of the lattice vector c.

Conversely, to convert from Cartesian to fractional coordinates, the inverse of the lattice vector matrix is used. This conversion is essential for linking theoretical models with experimental data, enabling a comprehensive understanding of crystal structures.

Wyckoff Positions¶

Wyckoff positions provide a systematic way to describe the locations of atoms within a crystal’s unit cell, considering the crystal’s inherent symmetry. Named after crystallographer Ralph Wyckoff, these positions are specific points in space that are equivalent due to the symmetry operations of the space group. Each Wyckoff position is denoted by a letter (e.g., a, b, c, ...) and has an associated multiplicity and site symmetry.

- Multiplicity: This indicates the number of equivalent positions within the unit cell for a given Wyckoff position. For example, a Wyckoff position labeled as 4e means there are four equivalent locations of that type in the unit cell.

- Site Symmetry: This describes the point group symmetry of the Wyckoff position itself. It represents the symmetry operations that leave the atomic site invariant. Site symmetry is labeled using Hermann-Mauguin notation (e.g., -1, 2, m, 2/m, etc.). A site with -1 symmetry has only an inversion center.

In essence, Wyckoff positions tell you where atoms can be located in the unit cell while still maintaining the overall symmetry of the crystal structure.

Finding Wyckoff Positions¶

Information about Wyckoff positions for each space group can be found in the International Tables for Crystallography, Volume A, or online resources such as the Bilbao Crystallographic Server (https://

Example¶

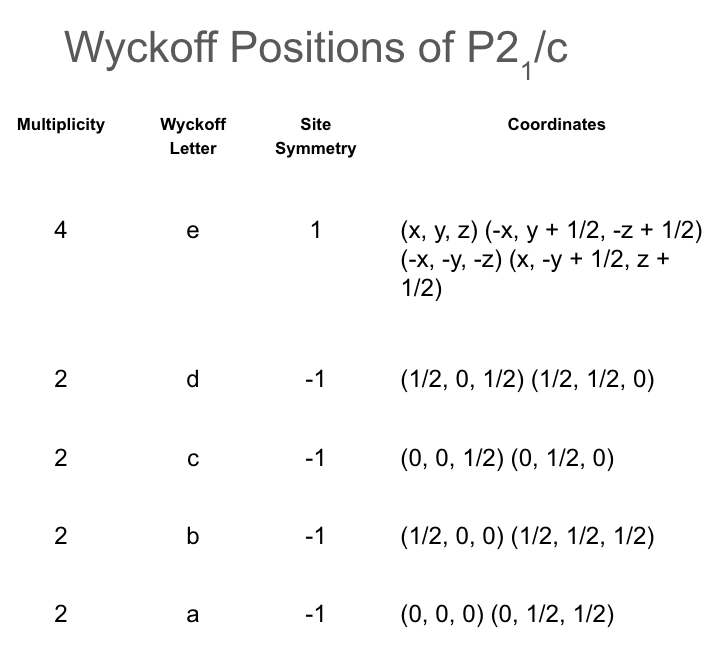

Wyckoff positions of space group.

Imagine a simple cubic crystal structure with space group as shown in above picture. One possible Wyckoff position is 4e at (0,0,0), and (0,0.5,0.5). This means there are two positions per unit cell at the origin.

Occupation¶

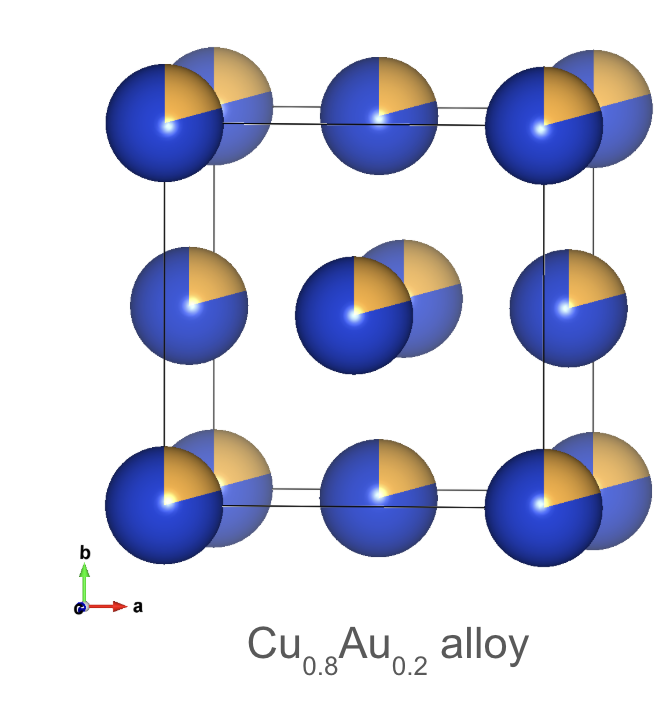

Disordered atomic arrangement in a alloy.

Beyond the defined positions within a crystal structure, it’s crucial to consider which atoms or ions actually occupy those sites. This is described by the site occupation. A site can be fully occupied by a single type of atom, partially occupied, or even co-occupied by multiple components.

The occupation value ranges from 0 to 1. An occupation of 0 indicates a vacancy, meaning the site is empty. Conversely, an occupation of 1 signifies that the site is fully occupied by the designated atom type. Partial occupation, with values between 0 and 1, suggests that the site is occupied by that atom type only a fraction of the time. In cases of co-occupation, multiple atom types may occupy the same site, each with its own occupation probability that contributes to the total occupation of 1.

Understanding site occupation is particularly important when dealing with structural disorder, such as in alloys. For example, high-entropy alloys (HEAs) exhibit exceptional mechanical, thermal, and magnetic properties due to their disordered structures. In these materials, different elements randomly occupy the available sites, leading to unique properties.

Computational approaches often require considering different possible arrangements of atoms on partially or co-occupied sites. This involves generating and evaluating various permutations of atomic ordering to accurately model the material’s behavior.

Experimentally, site occupation can be determined through techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) crystal structure refinement, which provides information about the atomic arrangement and occupancy within the crystal lattice.

Atomic Displacement Parameters¶

Atomic Displacement Parameters, also known as Debye-Waller factors, provide a measure of the deviation of atoms from their ideal positions within a crystal structure. This deviation is primarily due to thermal vibrations. Even in a seemingly rigid crystal, atoms are not static; they are constantly in motion, vibrating around their equilibrium positions. The extent of this vibrational movement is quantified by thermal displacement parameters, reflecting a crucial dynamic aspect of site properties. Larger thermal displacement parameters indicate greater atomic displacement.

Atomic Displacement Parameters can be either isotropic or anisotropic. Isotropic parameters, denoted as B, describe the displacement as equal in all directions. Anisotropic parameters, denoted as U, account for the fact that atomic displacement may vary depending on the direction. These anisotropic parameters are represented by a tensor, capturing the directional dependence of the atomic vibrations.

As temperature increases, the vibrational motion of atoms amplifies, influencing properties such as thermal expansion. This dynamic behavior is critical in linking static structural properties with real-world performance under varying thermal conditions, further connecting microscopic properties with macroscopic observable effects. Understanding thermal displacement parameters is essential for accurately modeling and predicting material behavior, especially at different temperatures.

Thermal Ellipsoid¶

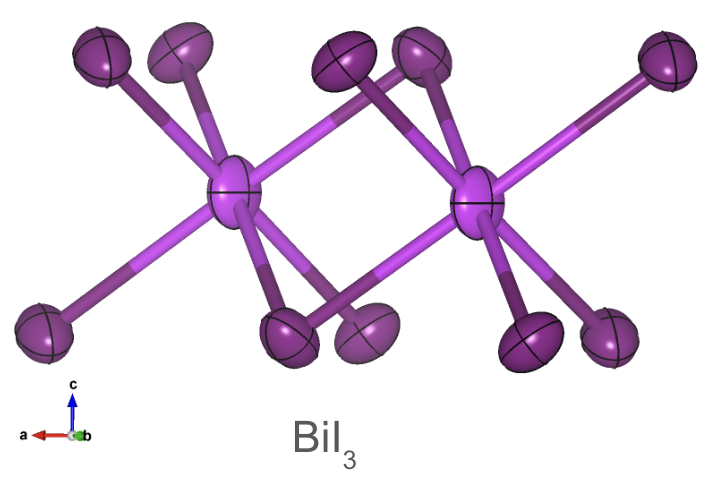

Thermal ellipsoids in . The principal axes of the ellipsoid represent the directions of maximum and minimum displacement.

To visualize thermal displacement, the thermal ellipsoid represents the probable range and direction of an atom’s vibrations. It serves as an intuitive model that mirrors how thermal energy affects atomic positions. The size and shape of the ellipsoid reflect the uncertainty in the atom’s position due to thermal motion. Larger ellipsoids indicate greater uncertainty and, by extension, higher thermal displacement.

Coordination Number¶

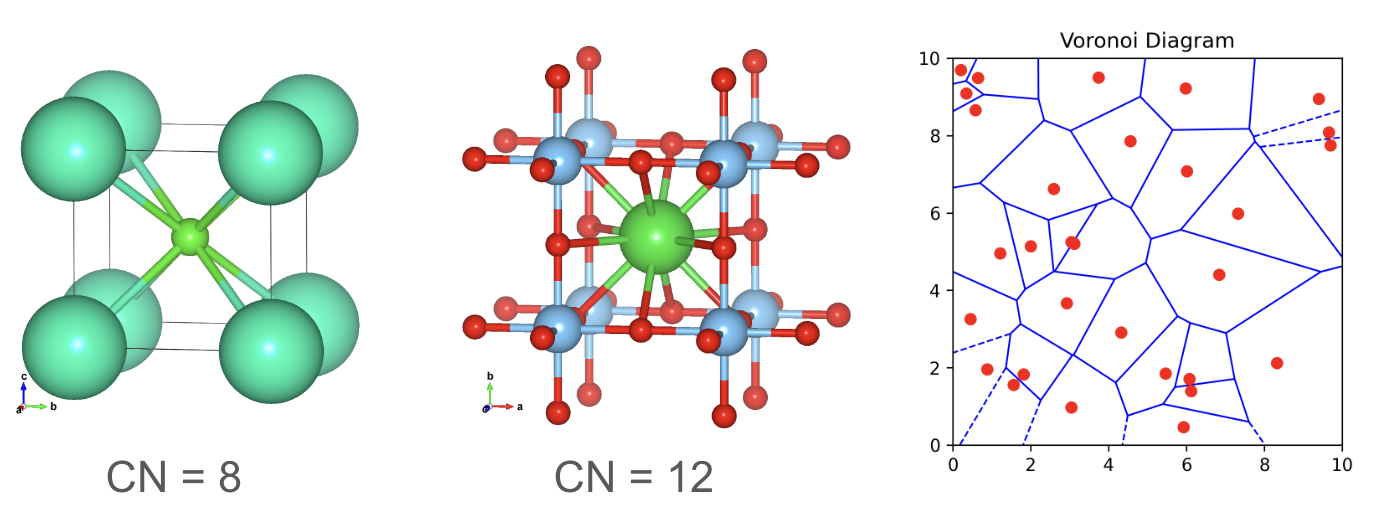

Local environment: Coordination number and Voronoi tessellation.

The coordination number quantifies the number of atoms directly bonded to a central atom. It provides valuable insights into the local environment and bonding characteristics of a particular site within a crystal structure. A higher coordination number generally indicates a greater number of bonds and potentially stronger interactions.

To determine the coordination number, one must identify the nearest neighbor (NN) atoms surrounding the central atom. Efficient algorithms, such as KD-tree searches (with a time complexity of O(log N)), can be employed to quickly locate these neighboring sites.

Another powerful technique for characterizing the local environment is Voronoi tessellation. This method constructs a Voronoi diagram by drawing perpendicular bisecting planes (or lines in 2D) between the central atom and all its neighbors. The resulting Voronoi cell represents the space closer to the central atom than to any other atom, effectively defining its local environment.

The coordination number, in conjunction with techniques like KD-tree searches and Voronoi tessellation, provides a comprehensive understanding of the atomic arrangement and bonding environment around a specific site.

Other Site Properties¶

There are several other site properties that play a significant role in determining the behavior of materials:

- Magnetic Moments: Intrinsic attributes arising from electron movements and spins, dictating how sites interact magnetically.

- Charge: Charge distribution at atomic sites impacts electron transport and chemical reactivity.

- Interatomic Forces: Determine the stability and mechanical properties of a material.