Introduction

Previous chapters have laid the groundwork for understanding materials from a computational perspective. We have explored the nature of computation itself, the critical role of databases like the Materials Project in organizing materials information, the intricacies of atomistic structures, and the theoretical underpinnings of simulation methods ranging from classical force fields to Density Functional Theory (DFT) and statistical techniques like Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC). We also saw how high-throughput computing frameworks leverage these tools to systematically explore material properties, for example, by constructing thermodynamic phase diagrams via convex hulls.

Despite the power of these methods, the quest for novel materials with tailored properties faces significant hurdles. The combinatorial space of possible materials—formed by varying composition, structure, and processing—is vast, far exceeding our capacity for exhaustive exploration through traditional experimental synthesis or direct first-principles simulation. While DFT provides high accuracy, its computational cost often limits simulations to relatively small systems (hundreds of atoms) and short timescales (picoseconds to nanoseconds), hindering the study of complex phenomena or the rapid screening of thousands of potential candidates. Classical simulations are faster but often lack the required accuracy or transferability, especially for materials with complex bonding or quantum mechanical effects.

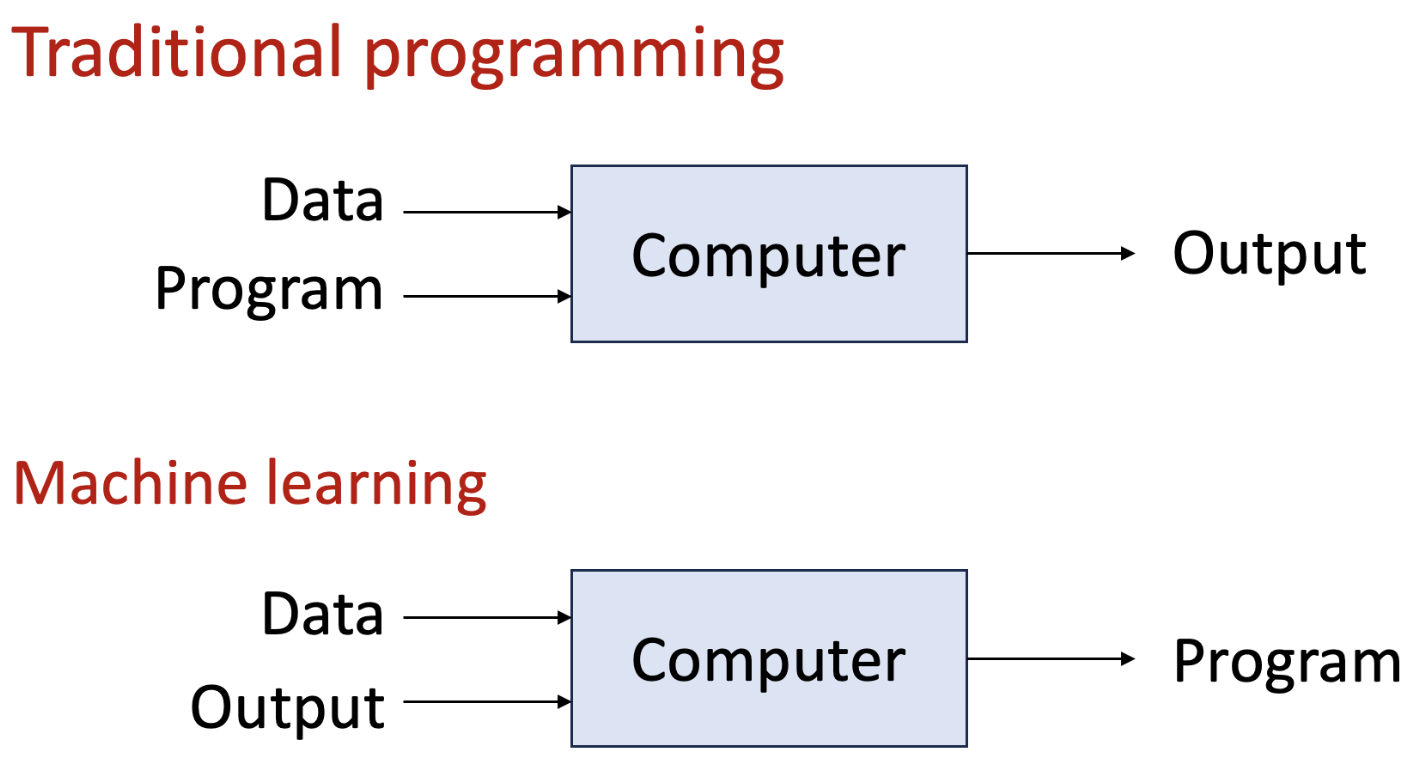

Machine learning vs. traditional programming. Machine learning takes a data-driven approach, generate a program based on data, while traditional programming relies on explicit rules and logic defined by the programmer.

This confluence of vast chemical space and computational limitations necessitates complementary approaches. Machine Learning (ML) emerges as a powerful paradigm designed to learn complex relationships and patterns directly from data. Instead of relying solely on simulating materials based on fundamental physical laws or predefined empirical models for every prediction, ML algorithms can be trained on existing experimental or computational data to build predictive models. These models act as efficient surrogates, capable of rapidly estimating material properties, classifying materials, or identifying promising candidates, thereby accelerating the materials discovery and design cycle.

It is crucial to recognize that ML does not supplant fundamental physics or simulation. Rather, it builds upon them. The curated data in materials databases serve as the foundation for ML training. High-throughput simulations provide the large, high-quality datasets essential for developing robust models. Our understanding of atomic structures and chemical principles guides the crucial step of representing materials in a format suitable for ML algorithms. In essence, ML provides a set of tools to extract maximum value and insight from the data generated by established methods, enabling exploration at unprecedented scales.

ML Tasks¶

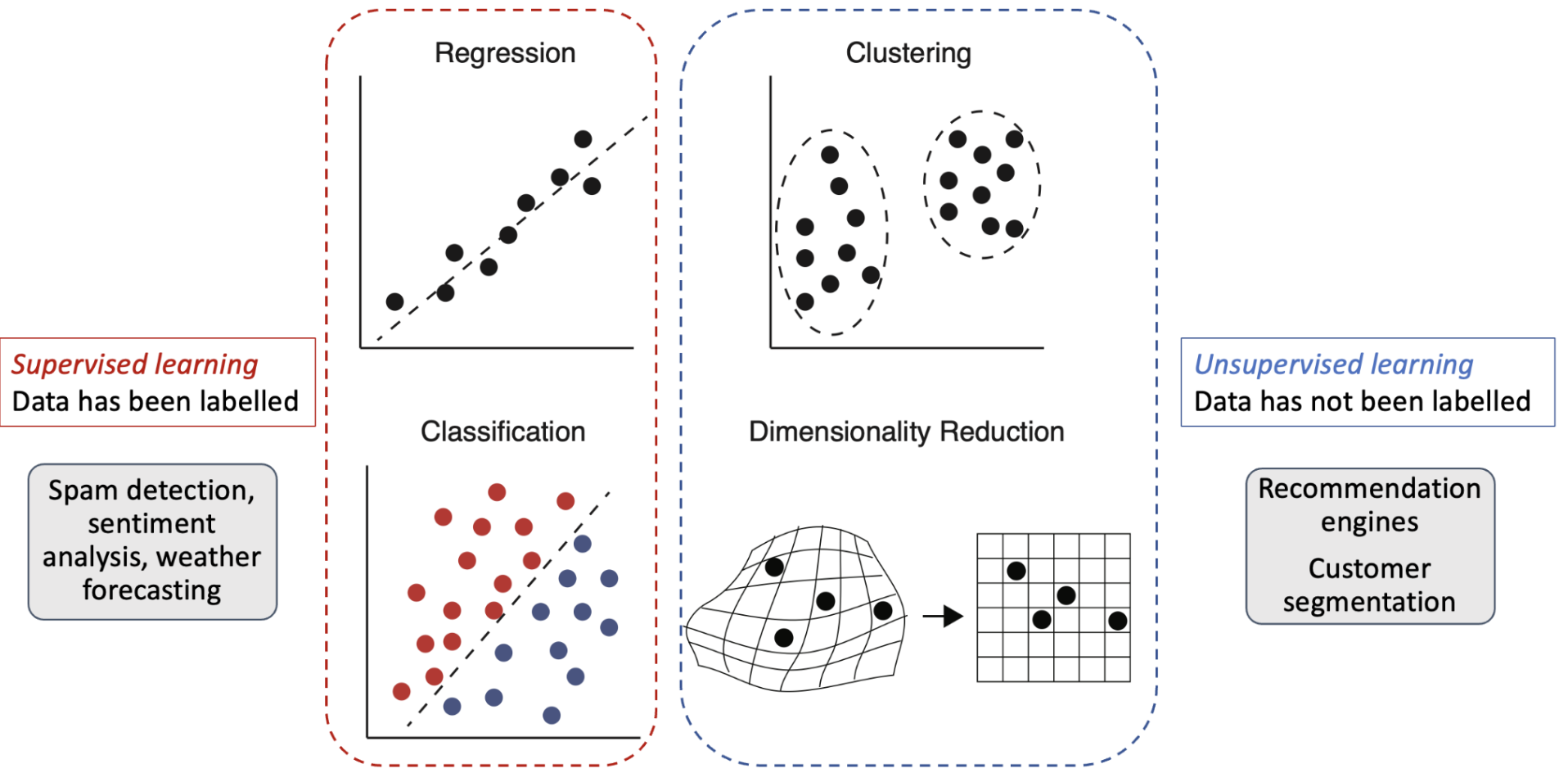

Two main categories of ML tasks: supervised learning and unsupervised learning.

ML tasks can be broadly categorized into three main types: supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning. Each of these categories serves different purposes and is suited for different types of problems.

Supervised Learning¶

Supervised learning is a type of ML where the model is trained on labeled data, meaning that each training example is paired with a corresponding target value or label. The goal is to learn a mapping from input features to output labels, allowing the model to make predictions on unseen data. Supervised learning can be further divided into two main subcategories:

- Regression: In regression tasks, the output variable is continuous. The model learns to predict a numerical value based on the input features. Examples include predicting material properties like band gap energy or thermal conductivity.

- Classification: In classification tasks, the output variable is categorical. The model learns to assign input features to predefined classes or categories. Examples include classifying materials as conductors, semiconductors, or insulators based on their properties.

Unsupervised Learning¶

Unsupervised learning is a type of ML where the model is trained on unlabeled data, meaning that there are no predefined target values or labels. The goal is to discover patterns, structures, or relationships within the data. Unsupervised learning can be used for tasks such as:

- Clustering: Grouping similar data points together based on their features. For example, clustering materials based on their structural or compositional similarities.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Reducing the number of features in a dataset while preserving its essential structure. Techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or t-SNE can be used to visualize high-dimensional data in lower dimensions.

- Anomaly Detection: Identifying unusual or unexpected data points that deviate from the norm. This can be useful for detecting outliers in materials datasets.

Reinforcement Learning¶

In reinforcement learning, a model learns to make decisions by interacting with an environment. The model receives feedback in the form of rewards or penalties based on its actions, allowing it to learn optimal strategies over time. Reinforcement learning is particularly useful for problems where the optimal solution is not known in advance and requires exploration and exploitation of different actions. Examples include optimizing material synthesis processes or designing experiments to discover new materials.

General Process¶

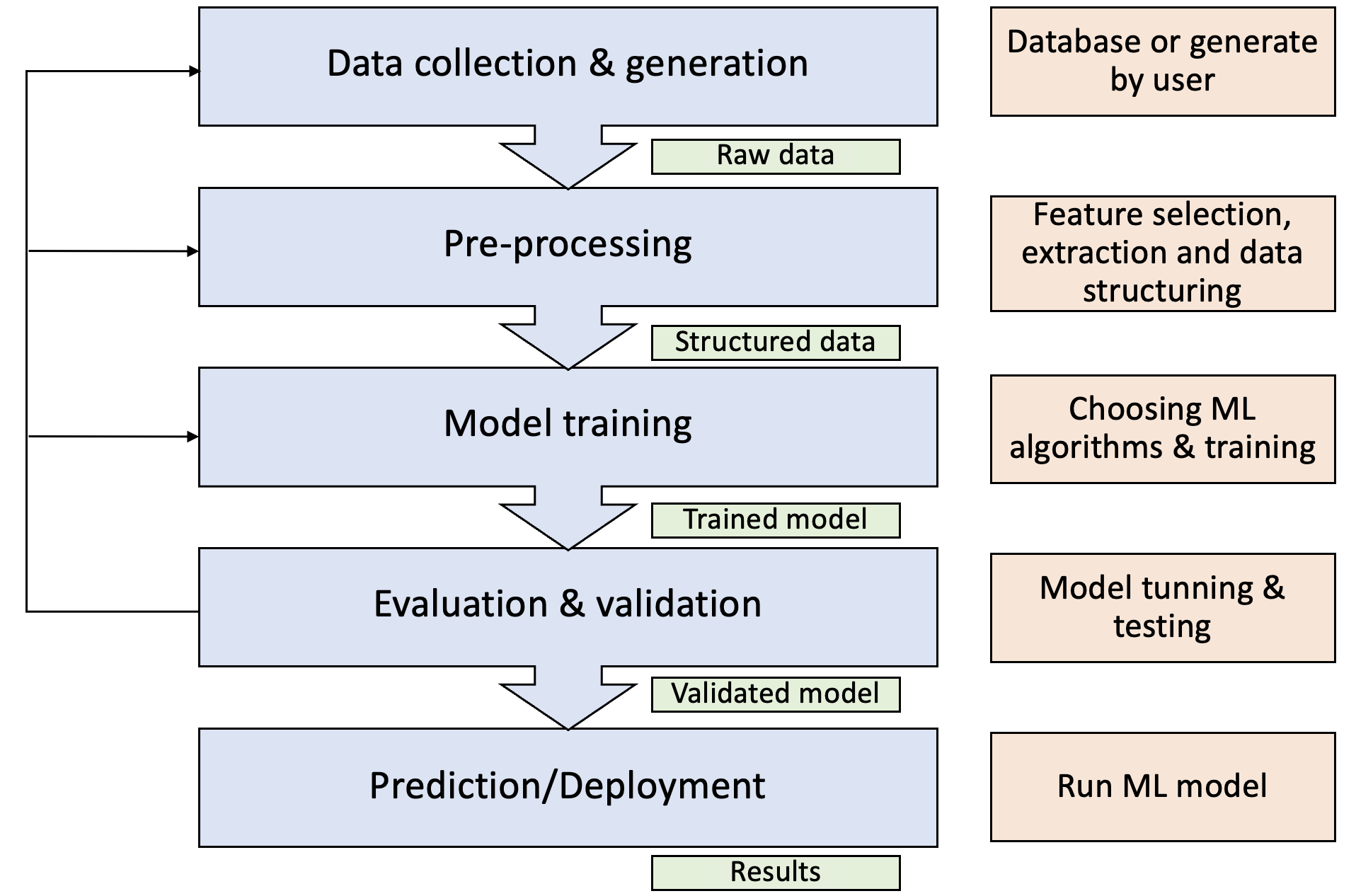

General process of how ML is applied to solve a general problem: data collection, pre-processing, model selection and training, evaluation and validation, and deployment.

The general process of applying ML to materials science can be summarized in the following steps:

- Data Collection & Generation: Gather relevant data from various sources, including databases, experiments, and simulations. We have already covered these topics in databases and high-throughput simulation.

- Feature Engineering: Transform raw data into meaningful features or descriptors that capture the essential characteristics of the materials. The description of crystal structures has been covered in atomistic structures I and II, and we briefly discuss the feature and descriptor in high-throughput simulation.

- Model Selection & Training: Choose an appropriate ML algorithm based on the problem type (regression, classification, etc.) and the nature of the data. Train the selected model using the training dataset, optimizing its parameters to minimize prediction errors.

- Evaluation & Validation: Assess the model’s performance using the testing dataset, employing metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score for classification tasks or mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) for regression tasks.

- Model Deployment: Once validated, deploy the model for real-world applications, such as predicting material properties or guiding experimental design.