Quantum Mechanical Model

Using force fields to model the interactions between atoms and molecules is a powerful approach to study the structure and properties of materials. However, most force fields are based on empirical parameters and approximations, which limit their accuracy and applicability to certain types of systems. For more accurate and general predictions, we need to use quantum mechanical methods that are based on the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics.

First-Principles¶

Also known as ab initio methods, first-principles method is based on solving the Schrödinger equation for a given system of particles. The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that describes how the wave function of a quantum system evolves over time. By solving the Schrödinger equation, we can obtain the wave function (Ψ) of the system, which contains all the information about the system, such as the positions and momenta of the particles, the energy of the system, and the forces acting on the particles. Properties can be obtained by applying different operators to the wave function. For example, the total energy of the system can be obtained by applying the Hamiltonian operator to the wave function. The many-body Schrödinger equation is given by:

where is the wave function of the system, is the Hamiltonian operator, and and are the positions of the electrons and nuclei in the system.

Born-Oppenheimer Approximation¶

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation states that the motion of the electrons is much faster than the motion of the nuclei, so we can treat the electrons as moving in the fixed potential energy field of the nuclei. Then the nuclei are treated as classical particles and only electrons are quantum particles. This allows us to solve the Schrödinger equation for the electrons separately from the motion of the nuclei, which simplifies the problem and makes it computationally feasible.

where is the total wave function of the system, is the nuclear wave function, and is the electronic wave function at a given nucleus positions. The electronic wave function is obtained by solving the time-independent Schrödinger equation for the electrons:

Density Functional Theory (DFT)¶

Solving the Schrödinger equation directly is computationally expensive and often infeasible for large systems. Density functional theory (DFT) is a method that approximates the wave function of a system by considering the electron density of the system. The electron density is a function of the positions of the electrons in the system and contains all the information about the system. By approximating the wave function in terms of the electron density, DFT reduces the computational cost of solving the Schrödinger equation and makes it feasible to study large systems.

The key idea behind DFT is the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, is that (i) the ground state electron density determines uniquely the external potential of the nuclei (ii) determines uniquely the many body wave function, and (iii) the ground state energy of the system is a unique functional of the many-body wave function. In total: .

The Hohenberg-Kohn theorems allow us to write the total energy of the system as a functional of the electron density:

where is the total energy of the system, ρ is the electron density, and is the energy functional of the system. The goal of DFT is to find the electron density that minimizes the total energy of the system, which gives us the ground state electron density and the ground state energy of the system.

This shift from dealing with wavefunctions with 3 variables to the electron density with 3 variables (x, y, z) makes the problem much more tractable. Therefore, by finding the electron density that minimizes the total energy of the system, we can determine the ground-state electron density and the ground-state energy of the system.

Kohn-Sham Equations¶

The high cost of solving the many-body Schrödinger equation can be reduced by introducing a set of auxiliary non-interacting electrons that have the same electron density as the true system. These auxiliary electrons are called Kohn-Sham electrons, and they are used to construct an effective potential that approximates the electron-electron interaction potential in the system. The Kohn-Sham equations are a set of equations that describe the motion of the Kohn-Sham electrons in the effective potential.

where is the effective potential that includes the external potential energy due to the nuclei, the Hartree potential () due to the classical electron-electron repulsion, and the exchange-correlation potential () that accounts for the effects of electron exchange and correlation. The Kohn-Sham equations are solved self-consistently by iterating between the electron density and the effective potential until self-consistency is achieved.

The charge density can be computed using:

where is the wave function of the -th electron and is the number of electrons in the system.

The key idea is to separate the total energy functional into terms that are easier to calculate and terms that are more difficult to calculate. The first three terms can be computed easily. The exchange-correlation energy is unknown and need to be approximated using different exchange-correlation functionals.

There are many different that have been developed: Local Density Approximation (LDA), Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), Hybrid Functionals, etc. Each functional has its own strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of functional depends on the system being studied and the properties of interest.

Basis Set¶

The wave function of the Kohn-Sham electrons is expanded in terms of a basis set of functions, which are used to approximate the wave function. The basis set can be chosen to be a set of atomic orbitals, plane waves, or other types of functions. In solid-state physics, planewave basis set is used:

where is a reciprocal lattice vector, are the expansion coefficients, and are the plane waves. The expansion coefficients are determined by solving the Kohn-Sham equations self-consistently. The more plane waves are included in the basis set, the more accurate the results will be, but the computational cost will be higher. Therefore, a compromise must be made between accuracy and computational cost.

Noted that the computation is done in the reciprocal space, and a k-points grid is used to sample the Brillouin zone. The number of k-points used in the calculation affects the accuracy of the results, with more k-points leading to more accurate results but higher computational cost.

Pseudopotentials¶

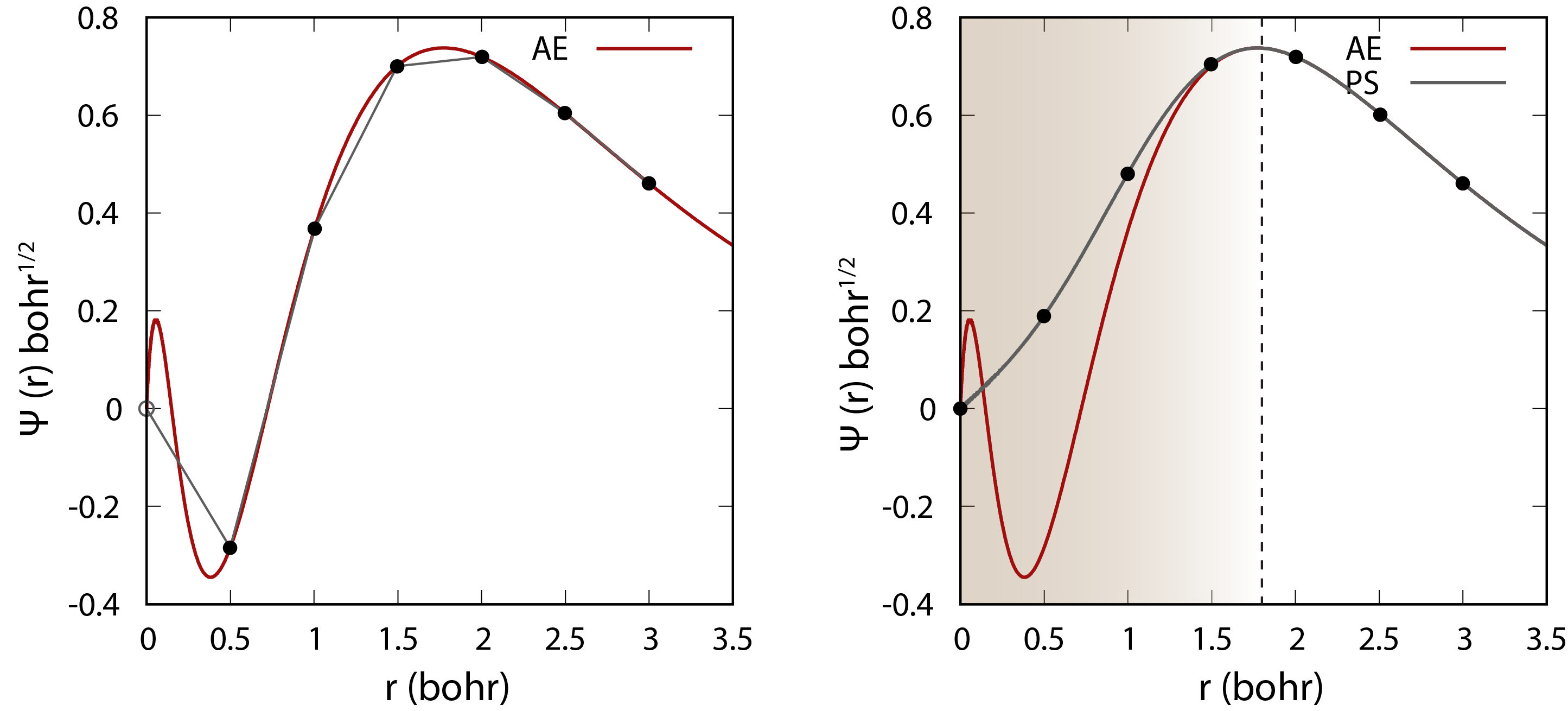

Comparison of the wavefunction between all-electron (AE) and pseudopotential (PS) calculations. The core electrons are replaced by an effective smooth potential in the pseudopotential calculation.

Psuedopotentials are used to replace the core electrons in the system with an effective potential that approximates the effect of the core electrons on the valence electrons because the core electrons are tightly bound to the nucleus and do not participate in chemical bonding. This allows us to reduce the number of electrons that need to be treated explicitly in the calculation. It also smooth out the potential near the nucleus, which makes the calculation converge faster with a much smaller basis set. There different ways of constructing pseudopotentials such as norm-conserving pseudopotentials (NCPP) and ultrasoft pseudopotentials (USPP).

Properties¶

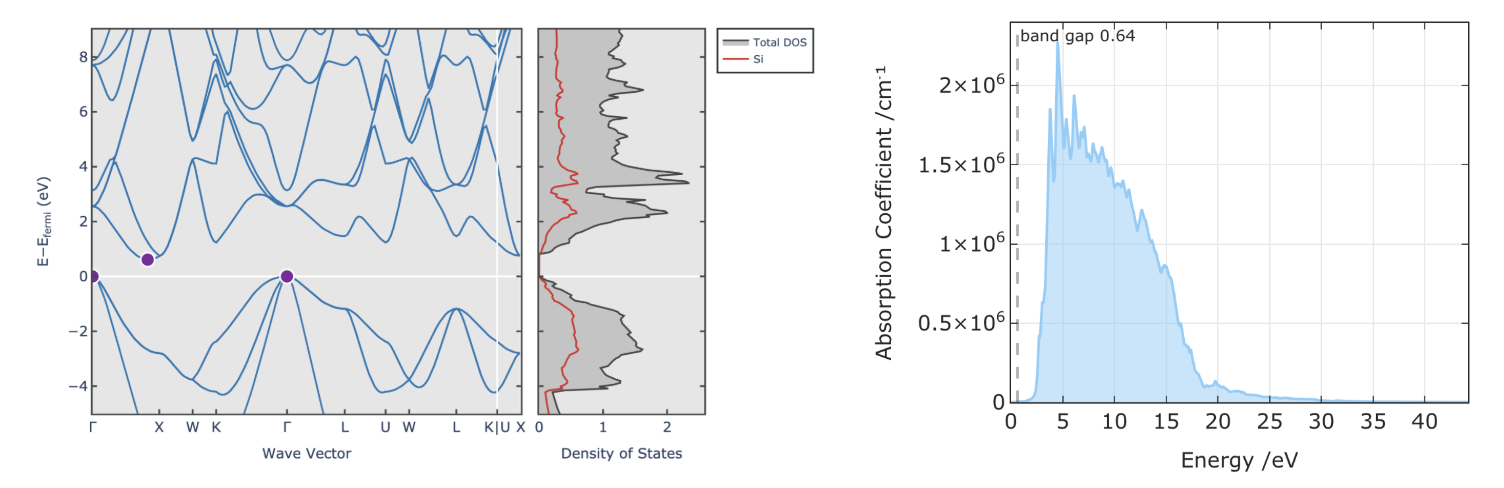

Band structure and optical adsorption spectra of Silicon calculated using DFT. It should be noted that the band gap of Silicon is underestimated.

Instead of compute the derivative of the total energy with respect to the position of the particles, the force can be calculated directly once the ground state electron density is determined using the Hellmann-Feynman theorem, which we need to determine to get the energy anyway.

Compared to classical force fields, DFT can provide more properties, such as electronic structure, bonding, and reactivity. DFT can be used to study a variety of systems, including molecules, solids, and surfaces.

However, DFT has some limitations, such as the underestimation of band gaps, the lack of dispersion (van der Waals) interactions, problematic treatment for the strongly correlated system, and the sensitivity to the choice of exchange-correlation functional. These limitations can be addressed by using more advanced functionals, such as hybrid functionals, and by including corrections for dispersion interactions.

Semi-Empirical Methods¶

Semi-empirical methods are a class of quantum mechanical methods that are based on a combination of empirical parameters and quantum mechanical principles. These methods are less computationally expensive than first-principles methods and are often used to study large systems that are beyond the capabilities of first-principles methods.

Semi-empirical methods are based on approximations and simplifications of the Schrödinger equation, which make them computationally efficient but less accurate than first-principles methods. Some common semi-empirical methods include the tight-binding method, the extended Hückel method, and the semi-empirical molecular orbital (SEMO) method.